To celebrate the October 13th release of my forthcoming debut novel, King of Shards, I will be featuring one new blog entry a day about a different Judaic myth for 36 days. Today’s entry is on the Tetragrammaton, The Name of God,

Day 14: The Tetragrammaton, The Name of God

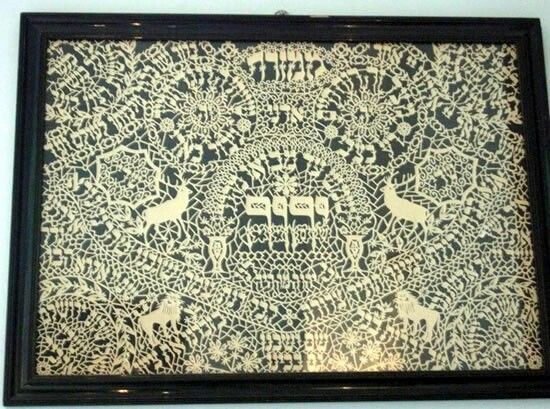

All that exists in the universe comes from God’s holy name, which is spelled יהוה, YHVH. The name has great power. It can bring life to inanimate things and it can bind evil forces so they have no power over a person. King Solomon used the name to bind demons to subdue and control them during the construction of the Temple, and Rabbi Judah Loew used it to bring life to a golem, a man of clay, to protect his village from a pogrom.

In ancient times, the pronunciation of the name was a secret known only to the holiest few, and carefully guarded because of its great power. On the holiest of days, Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, the High Priest, after having ritually purified himself, entered into the Holy of Holies, the inner sanctum of the Temple, and pronounced the divine name.

Today, after the destruction of the Temple, knowledge of its pronunciation is lost. However, in each generation there is a Tzaddik Ha-Dor, a righteous person of their generation, who knows its secret pronunciation. In the past, such sages as Rabbi Adam, Rabbi Judah Loew, and the Ba’al Shem Tov all knew the secret pronunciation, and used it to perform miracles.

However, pronunciation of the name is strictly forbidden, and he who does has no place in the Messianic age. And one must not write the holy name down, unless one is a sofer, a Torah scribe. The name is forever holy and full of power.

The Myth’s Origins

The Tetragrammaton, or the four-letter name of God, is written 6,828 times in the Jewish scriptures. Based on evidence found in the Mesha Stele from the 9th century B.C.E, from the “J” source in the Torah scriptures, and other ancient Greek and Hebrew texts, scholars believe that the name was once pronounced openly in ancient times. The great Jewish philosopher Maimonides claimed that the name was pronounced daily in the Temple services during the priestly blessing of worshippers. The Talmud states that in the last generations before Jerusalem fell, priests chanted the name in a low tone, and so listeners could not discern its pronunciation. And when the Temple was destroyed, the name was no longer spoken aloud, though the pronunciation was still taught in rabbinical schools.

The Mishnah, or biblical commentary, states that those who pronounce the name will have no part in the Messianic era. This is why Jews today refer to God as HaShem, “The Name,” or Adonai, “Lord.” Additionally, the name of God, if written down, cannot be disposed of as one would normal trash. Instead, such writing must be stored in special places, or buried in a consecrated grave like a person. Religious Jews will not write down the holy name, and instead substitute a different letter in the Tetragrammaton. In English, you will see religious Jews write out God with a dash, as in “G-d.”

The Hebrew letters יהוה correspond to YHVH (or YHWH) in English. Since biblical Hebrew has no vowels, early Western scholars added their own, and YHWH became YaHWeH. This in turn entered English as Jehovah. Though the original meaning of the divine name is unclear, many scholars believe the name to mean “to be”, “exist”, “become”, or “come to pass.” In fact, when Moses is commanded by God to go down to Egypt and confront the Pharoah, he asks God, “Whom shall I say sent me?” and God says to say, “I AM THAT I AM…Thus shall you say to the children of Israel, I AM has sent me unto you.”

The identification of God’s name with divine power may come from the notion that his name equates to being itself. Hence the ability of the divine name to bring life, or being, to inanimate things. But since such power of creation is reserved for God himself, and none other, one is forbidden from using it, except in the most sacred of all prayers.

Some Thoughts on the Myth

I have always been fascinated with the notion that God’s name is some form of “to be” or “to exist.” Despite Judaism having no obvious connection to Eastern traditions, here is a very real and concrete piece of evidence that there may have been crossover influence. Hinduism ,and Buddhism especially, focus on consciousness as the source of all being. And here we have the Judaic God stating that his name is “I am that I am.” Or, according to other translations, “I will be what I will be.” The Tetragrammaton itself is likely some form of a verb meaning “to be”,”to exist,” or “to become.” God is basically telling Moses he is being itself — transcending all former notions of gods as anthropomorphic figures of water or sky or stars. This God is different, he tells Moses. He is the substratum that underlies all existence, being itself.

Rabbis of the first Temple, speaking Hebrew as their daily tongue, likely knew the pronunciation of the divine name but also its meaning. They were worshipping the God of Being, which transcends all other deities and concepts. You can’t have water or sky or stars or anything without being. This is a very Eastern concept, and one that our Western scientific-materialist view often rejects. Of course, the scientist says, there is still a universe without consciousness. But the concept of a clockwork universe, one that runs without any observer to watch it all pass, is relatively new.

I’ve often wondered if the ancient Israelites, influenced by Eastern traditions, began to see their unitary God as being more than the ruler of all other gods and people, but as consciousness or being itself. As Eastern traditions have shown us, our minds are both are best friends and worst enemies. I wonder if the ancient priests and rabbis saw the power of their own minds, their consciousnesses, and recognized their awareness as aspects of a greater, encompassing being whom they called YHVH, or “to exist,” and worshipped this power as divine?

What happened later seems to me like a fetishization of the divine name, the letters themselves being imbued with power. A beautiful concept of equating God with Being itself was reduced to four letters and sounds, for which replication was forbidden, except by a chosen few adepts. To me this seems like a form of idolatry. Do we worship the letters or the being they represent? Why is the word “To Exist” so holy that only the most holy can write or speak it? Thoughts to consider.

(As a side note, there is a fun story by Ted Chiang about the Tetragrammaton and other divine names called “Seventy-Two Letters.” I enjoyed the story, but I was left wondering why he removed all semblance of Judaism from the story, which was so obviously influenced by Kabbalistic and Judaic ideas.)

Tomorrow’s Myth: The Guf, the Treasury of Souls

1 Pingback