To celebrate the October 13th release of my forthcoming debut novel, King of Shards, I will be featuring one new blog entry a day about a different Judaic myth for 36 days. Today’s entry is on Gehenna and punishment.

Day 10: Gehenna and Punishment

Gehenna is one of the seven things created before Creation. It is a place of punishment and darkness. It lies far beyond the firmament and it’s as big as the Garden of Eden, that is to say, it is endless. Gehenna’s fires were kindled on the night of the eve of the very first Sabbath, and they continue to burn today. Their fires are so bright that the sun turns red in the evening. The fires of Gehenna will never be extinguished. In addition to fire, Gehenna rains down a heavy hail, which is worse than the ever-burning flames.

When a wicked person dies, his soul is taken to Gehenna by the angel Dumah. There, with the help of the three angels of destruction, Af, Mashit, and Hema, they command many legions of of avenging angels. So loud is the cry from these avenging angels that their shouts reach all the way to heaven. The sinners, suffering in their torment, cry out to heaven for mercy, but the angels in heavy can barely hear them above the din, and so they do nothing.

For six days, without pause, the angels punish the sinners, but on Sabbath, they are given respite from their suffering to ponder their sins. The sinners who kept the Sabbath while alive are taken to twin mountains of snow to cool their bodies from Gehenna’s unending flames. But those who did not observe the Sabbath are given no respite. The angels rest, as God commanded them, until the end of the Sabbath. Then they drag the wicked back to the dungeons of Gehenna to be punished again.

Both Jews and Gentiles suffer in Gehenna. But God’s judgment is not eternal. After one year of suffering, when the body has fully decomposed, the souls of the sinners fly up to God to await the World to Come, the Messianic age. This is not on their account, but on account of the righteous that God forgives them. The very righteous do not enter Gehenna, but go directly to God. And the very wicked spend the full twelve months suffering. But those who are not fully wicked suffer for less than a year. This is why we only say Kaddish, the Mourner’s Prayer, for eleven months for our departed loved ones.

The Myth’s Origins

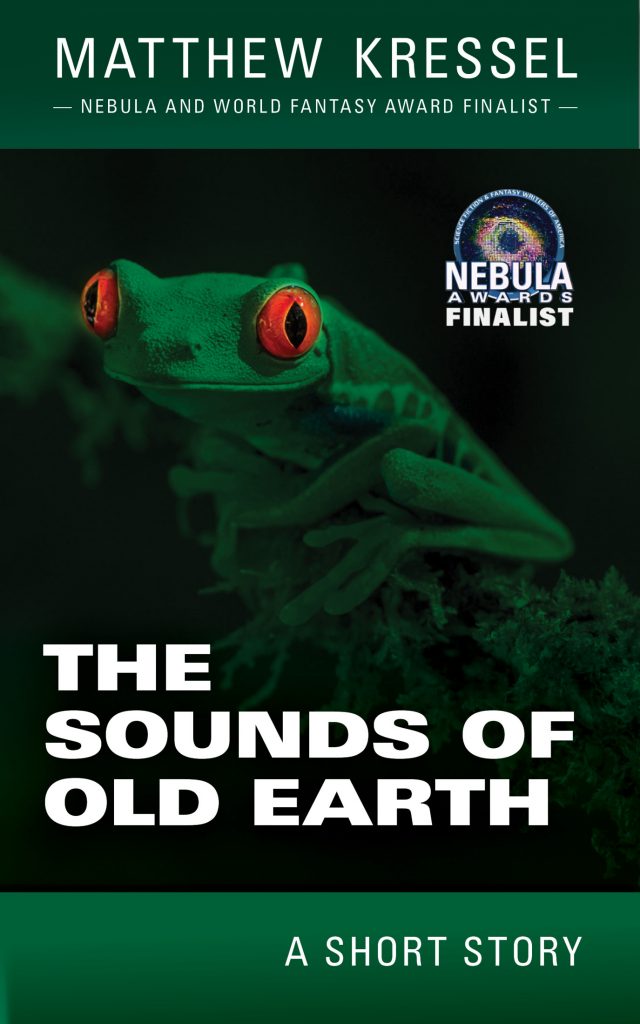

Ancient tombs in the Valley of Hinnom

In ancient times, various pagan cults such as those that worshipped Baal and Molech, sacrificed their children to gods in the Valley of the Son of Hinnom, or Valley of Hinnom. In Hebrew, this was called Gai Ben-Hinnom, and it was because of this child sacrifice and the constant sacrificial fires that it was seen as a place of evil. This name morphed, over time, into Gehinnom, or Gehenna in English.

Joshua 15:8 and 18:16 speak of the dimensions of the valley, and Isaiah 30:33 speaks of a place of burning. But it is in the Mishna, or biblical commentary, that most of the stories of Gehenna take on a new life. Gehenna, here, takes on the role of Hell, a concept the early Jews borrowed from the Persians. In the Talmud, Rosh Hashana 16b, it elaborates on the concept of the Book of Life we spoke about in an earlier post when it says, “The thoroughly righteous will forthwith be inscribed definitively as entitled to everlasting life; the thoroughly wicked will forthwith be inscribed definitively as doomed to Gehenna, as it says. And many of them that sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life and some to reproaches and everlasting abhorrence.”

And Rosh Hashana 17a says, “Wrongdoers of Israel who sin with their body and wrongdoers of the Gentiles who sin with their body go down to Gehenna and are punished there for twelve months. After twelve months their body is consumed and their soul is burnt and the wind scatters them under the soles of the feet of the righteous as it says, And ye shall tread down the wicked, and they shall be as ashes under the soles of your feet.”

And Genesis Rabbah says, “The wicked are darkness, Gehenna is darkness, the depths are darkness.”

Dumah, the ruler of Gehenna, takes his name from the Hebrew word for silence and the land of death. And as for the respite on the Sabbath, it is said that even God himself observes the Sabbath, and therefore so do his avenging angels. Af, Mashit, and Hemah, Dumah’s commanders of the avenging legions of angels, take their names from the Song of Solomon, 3:8, “They all handle the sword, and are expert in war; every man hath his sword upon his thigh, because of dread in the night.”

Some Thoughts on the Myth

Unlike Christian myths of Hell, the Jewish Gehenna is not a place of eternal punishment. It is seen as a place where one’s sins are burned off like dross, so that the soul may be purified. There she is brought back into the arms of God, to await the final redemption. This is to emphasize that God is ever merciful.

The early Jews, as exemplified in the tale of the binding of Isaac, tried to distance themselves as much as possible from the child-sacrificing cults of the time. Because of this, the fires of Hinnom must have been viewed as a place of horror (not to mention the fear for one’s children!). That this morphed into dozens of tales about a place of eternal fires and punishment is proof of the great imagination of the early rabbis. Christianity of course elaborated and expanded on the various myths of Hades and Gehenna to form their view of Hell as the place of eternal damnation. But in Judaism’s Gehenna, there is a path to redemption even for the most wicked.

Also, at least in Conservative and Reform synagogues, you won’t hear much talk of the afterlife or Gehenna, if at all. The reason is that in Judaism, the focus is always on this life. This world. The work to be done is not for some future redemption in an afterlife, but to assist in this Creation, to finish perfecting the world that God began. And so, though there is a place of punishment for sinners — the world would not be just without one — the concept of punishment after death is not central to its teachings.

What you will see often in these stories is the same recurring theme: hope, tikvah in Hebrew. For a people long-exiled, long-suffering, hope is what enabled them to carry on as a culture and a people. I don’t think there is any stronger message than to say that there is still hope for the soul even in Gehenna, even in Hell.

Tomorrow’s Myth: The Four Who Entered Paradise