Today, October 13, is the release day of my debut novel, King of Shards, and for the last thirty six days I have been featuring one new blog entry a day about a different Judaic myth. I hope that along the way these posts have opened your eyes to the rich mythology and beauty in this ancient tradition. It’s been fun and educational for me as well, because in my research I’ve discovered fascinating things I did not previously know. Thank you for sharing this journey of discovery with me!

Today’s last entry is on The Lamed Vav, The Thirty-Six Hidden Righteous.

Day 36: The Lamed Vav, The Thirty-Six Hidden Righteous

In every generation there are thirty-six just men who uphold the world, the Lamed Vav Tzaddikim. Each is blessed to be able to glimpse the Shekhinah, the Divine Presence. And because of their merit, the world continues to exist. If one were to die, another is immediately born to take his place. God permits the world to exist on account of their righteousness. If any one were to cease being righteous, the world would be destroyed. Because in Hebrew the letter ל lamed is thirty and the letter ו vav is six, we call these thirty six hidden saints the Lamed Vav.

Their chief traits are humility, selflessness, and anonymity. They are so anonymous, in fact, that you or I could be a Lamed Vavnik and not know it. The Lamed Vav work ordinary jobs, earning a living by the sweat of their brow as tailors, blacksmiths, shoemakers, and other humble professions. Those who live and work among the Lamed Vav never suspect they walk in the company of a saint. If, by chance, a Lamed Vavnik is exposed, he will fiercely deny it. It is also said that if a Lamed Vavnik discovers his hidden nature as one of them, he will immediately die, and another will be born to take his place.

The Lamed Vav perform small acts of kindness and righteousness that may seem insignificant in the eyes of passers by. But God watches and knows the sum of these small acts serve to uphold the world. Without such acts, the world could not exist. Therefore we call these Lamed Vav the Pillars of Existence. In times of great conflict, the Lamed Vav emerge from their hiding places to use their secret knowledge of kabbalah to avert disaster. After, the Lamed Vav return to their lives of anonymity in a new community.

The Myth’s Origins

This myth may originate from Genesis Chapter 18, where Abraham pleads with God not to destroy the righteous along with the wicked in Sodom. “Wilt Thou indeed sweep away the righteous with the wicked? Peradventure there are fifty righteous within the city; wilt Thou indeed sweep away and not forgive the place for the fifty righteous that are therein?” And then after some more bargaining, Abraham gets God down to ten people. “Oh, let not the Lord be angry, and I will speak yet but this once. Peradventure ten shall be found there.’ And He said: ‘I will not destroy it for the ten’s sake.” So if ten righteous persons could be found in Sodom, God wouldn’t destroy it.

God destroyed the world once, in the Great Flood, to erase its wickedness. So what prevents him from doing it again? The ancient rabbis posited answers: In Genesis Rabah 35:2, it says, “The world possesses not less than thirty men as righteous as Abraham.” But later, in the Talmud, in Tractate Sanhedrin 97b, comes the following passage, “The world must contain not less than thirty-six righteous men in each generation who are vouchsafed the sight of the Shekhinah’s countenance, for it is written, Blessed are all they that wait [lo] for him; the numerical value of ‘lo’ is thirty-six.” In this passage, the Hebrew word “for him” is “lo” which in Hebrew is spelled lamed vav, לו , i.e. 36.

The number 36 has a mystical connotation too. In Hebrew, letters are also numbers, and the number eighteen spells out the Hebrew word for life or living, חַי, chai. So twice 18, twice life is 36. This is the most likely reason this number stuck.

Among some versions of the myth, the promised Messiah will be a Lamed Vavnik, who is also known as the Tzadik Hador, the righteous person of this generation. If the world is deemed ready, the Tzadik Hador will emerge as the Messiah.

Some Thoughts on the Myth

Among the many gems, this is my favorite Judaic myth. It posits that anyone you meet might be the one who is responsible for upholding the world, therefore you should treat everyone with the utmost respect. But it also means that you could be one. You might be responsible for upholding the world. And therefore you should strive to be kind and humble and righteous in order that the world continues to exist.

This myth appears in many places throughout literature and pop-culture, but it’s not widely known outside of Jewish circles. Perhaps it’s most well-known usage is in Michael Chabon’s The Yiddish Policemen’s Union, where one character is presumed be the long sought-after Tzadik Hador, the righteous person of his generation who might be the Messiah. But my favorite Lamed Vav story is the novel The Last of the Just by André Schwarz-Bart, about an ancestral line of Lamed Vav (in his novel, the Lamed Vav inherit the role from their fathers). Its steady build climaxes in a powerfully devastating ending during the Holocaust. It’s one of the best and most moving novels I’ve ever read.

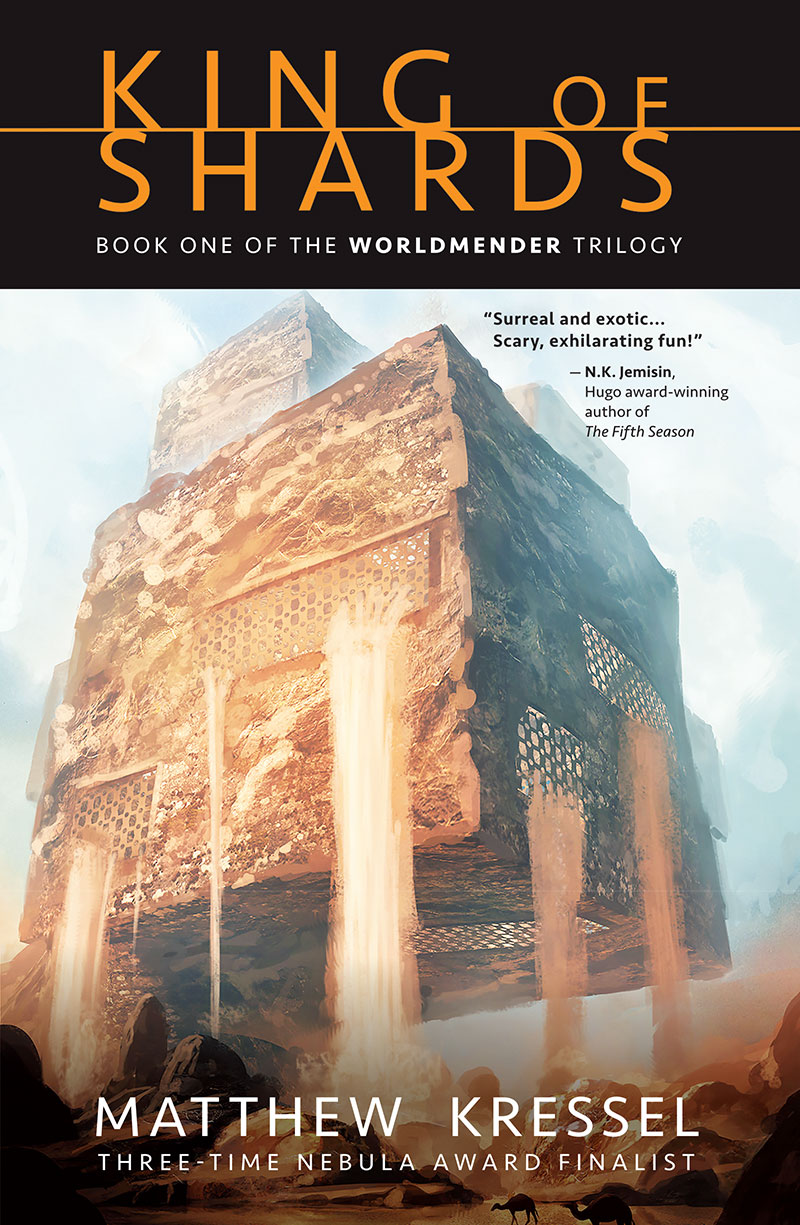

I have been so enamored by this myth that I actually wrote a book about it: King of Shards.

In King of Shards, Daniel Fisher is abducted from his wedding by none other than Ashmedai, king of the demons, and is ushered down to the hell world known as Gehinnom (Gehenna). There he learns he is a Lamed Vavnik and that a group of demons have discovered the names of the hidden Lamed Vav and are killing them. The demons hope that by killing the Lamed Vav, the earth will be destroyed, and the abundance and peace that has long been denied them will be theirs at last. In order to stay alive and protect the other Lamed Vav, Daniel must team up with Ashmedai, the demon king, who has be dethroned and cast out of Sheol. Together, saint and demon, must race across the fragment universe of Gehinnom while chased by a fearsome demon army in order to get back to earth and save the Lamed Vav. The only problem is that Ashmedai may not be the most trustworthy of partners. He is a demon after all.

King of Shards incorporates many of the myths discussed here in this blog series, such as The Lamed Vav, Gehenna, Sheol, The Shattered Vessels, The Ziz, and many more. And while I reference Jewish mythology often, I never let myself be constrained by it. So while King of Shards is based on Jewish myth, much of the mythology in the book is my own. Often I elaborated and expanded upon extant myths in the same way as Jews have been doing for thousands of years. What I hope I have created is work of adventure fantasy fiction that anyone might enjoy. But you folks who’ve stuck with me for these last thirty six days might get to enjoy the book just a little bit more.

Thank you so much for sharing this journey of discovery with me!

King of Shards is out today, and you can get a copy in print, ebook, and audio book.

|

|

|

|

May 31, 2018 at 6:44 pm

Thank you for the information. I first heard of the Lamed Vav in the book “When You Meet the Buddha on the Road Kill Him” by Sheldon Kopp. Over the intervening years I have mentioned it to a number of Jewish friends in a effort to learn more. None have been aware of the myth.

The concept immediately fascinated me as have other meaningful religious myths.

Please add me to your mailing list. The link did not work.

June 1, 2018 at 8:14 am

Hi Richard, it looks like you’re already on the list. Thanks.

October 5, 2018 at 5:31 pm

Interesting storyline! Asmodeus is also a major antagonist in Tobit, my favourite (non-canonical) Jewish book.

In regard to the lamedvavniks… Though long-standing tradition depicts these righteous “ones” as individuals, there’s a lot of evidence in scripture and in gematria to support the contention that they are actually couples.

Numerologically, it’s straight-forward… Life = Chai = 18; and 18 + 18 = 36.

Scripturally, consider the marriage stories that dominate the biblical narrative, without many of which the world as we know it might well have expired at some critical juncture. Think of Adam & Eve, Abraham & Sarah, Isaac & Rebecca, Jacob & Rachel, Jacob & Leah, and let’s not forget Achashverosh & Esther. Each of these pairs (and many more besides) made it possible for this epic story to continue unfolding.

If this perspective is valid, then the number of lamedvavniks in the world is not limited to thirty-six individuals – or even to thirty-six couples. It is liberated by the possibilities inherent in shared oneness.

peace