To celebrate the October 13th release of my forthcoming debut novel, King of Shards, I will be featuring one new blog entry a day about a different Judaic myth for 36 days. Today’s entry is on the Shattered Vessels.

Day 3: The Shattered Vessels

Before time existed, there was just God, and his light filled the universe. There was no place that God did not exist. At some point, God decided to create a world. But God recognized that there was no place to build such a world, because his presence filled the universe. So God withdrew himself away from a part of the universe, drawing in his breath, and there he would make a world. A void was formed, dark and empty, and then God said, “Let there be light!” The light entered into this void and formed, in succession, ten vessels filled with God’s primordial light.

Yet the vessels weren’t perfect. Unable to contain God’s immense and overwhelming light, the ten vessels shattered. Billions of holy sparks were scattered about the great void like the stars in heaven. This is why humanity was created, to gather the holy sparks which have been scattered across creation and to bring them into wholeness again. This is also why Jews have been spread about the Earth, so they might raise the fallen holy sparks from around the globe.

It is said that when all the holy sparks have been gathered, the primordial vessels will be restored, and the world will finally be repaired. This is the Messianic era that humanity so eagerly seeks. Therefore, it should be every person’s greatest desire to lift these fallen holy sparks wherever they find them and to elevate them to holiness by being righteous. This is known as Tikkun Olam, the Repairing of the World. It is said that when the repair nears completion, even God himself will assist in the final rebuilding and lifting of the sparks.

The Myth’s Origins

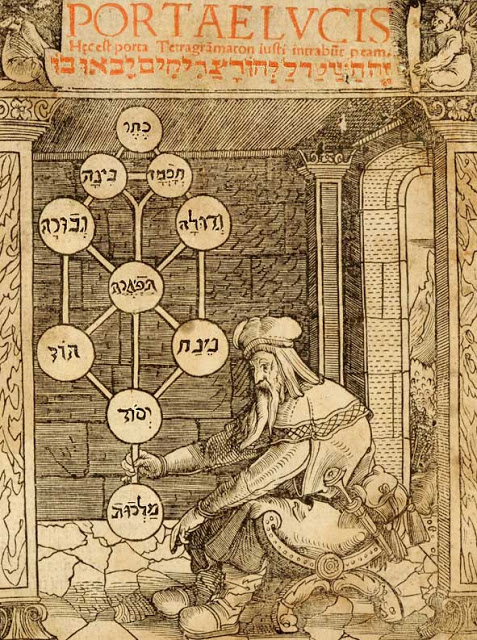

The myth of the Shattered Vessels (Shevirat Ha Keilim in Hebrew) attempts to explain the origin of evil in the world and the cosmology of creation. The book of Genesis speaks of kings that ruled over the land of Edom before any kings ruled in Israel. Genesis 36:31: “And these are the kings that reigned in the land of Edom, before there reigned any king over the children of Israel.” These eight kings ruled and died before Israel was created. Rabbi Isaac Luria, known to his devotees as the “Ari,” in the 16th century elucidated the mystical interpretation of the Zohar (the Book of Splendor) and ideas first expounded by Moshe Cordovero (a 16th century Jewish scholar), to form the myth of the Shattered Vessels.

God’s presence, he said, filled the universe, and this presence was known as the Ein Sof, or the endless. In order to create a finite world in the endless sea, God had to contract himself. This is known as the Tzimtzum, or contraction. Because God’s light was too powerful and overwhelming, it would destroy anything it touched. So his light had to be reduced by degrees. These are the “vessels” that contained God’s light, acting as filters. There are ten of them, each with different properties, and they are known as the Sephirot. The lower seven vessels, because they were “immature,” still could not contain God’s stepped-down light, and they shattered to form the klippoth, sparks or shards. These sparks fell down to the “ground,” where they remain today, awating their return to God by righteous acts of the living.

The Ari took the biblical phrase about the kings of Edom and ideas from Moshe Cordovero to form his myth of destruction of the primordial worlds. Furthermore, though the vessels shattered, God’s light clung to these many fragments like “residue,” and it is these fragment sparks that have become our material reality, which the Ari considered demonic in nature. Our world, the Ari said, is flawed. It is our goal, therefore, to raise these broken sparks back to holiness, which is done by observing God’s commandments and living a righteous life. But the sparks, since they contain God’s divine energy, can also be used by darkness. Thus it is not God who created evil, but evil instead is the result of this divine energy being used not to bring the sparks back to God and holiness, but to alternate, i.e. darker ends.

Alternate Versions and Elaborations

Ari’s myth of the Shattering of the Vessels is one of the most common myths found in Kabbalah, or the mystical interpretation of Judaism. It elaborated and refined the ideas of Moshe Cordovero’s Sephirot, or ten divine emanations. It has been expounded upon by many sages for centuries and many versions of this creation story exist.

In one version, all the ten Sephirot shatter together. In another version, only the lower seven Sephirot break apart. In some myths, each Sephirah (individual vessel) has its own ten vessels. In addition to these variants, some myths posit different worlds between each emanation of God. For example, one myth posits the Adam Kadmon, a primordial universe, which is too raw to contain matter. From this world comes the next, less raw universe, the Akudim, which becomes the first world to contain the ten divine lights of the Sephirot. Following this world, comes the world of Nikudim or Tohu (darkness), from which our world emerges (after the shattering).

Some Thoughts on the Myth

It’s interesting to note that this myth posits an imperfection in creation. God created the vessels, which were faulty, and they shattered. Was this intentional? Some versions of the myth say, yes. The shattering was necessary because it was intended to split the holy light into many distinct qualities. In order to introduce diversity into creation, the light had to shatter into all the spectra of life. In addition, allowing for the possibility of darkness gives humanity the opportunity to choose between good and evil. This is how God’s characteristics of Judgment (Gevurah) and Mercy (Chesed) are revealed in the world. Otherwise, all would be one with God, and there would be no free will.

Another myth suggests that the first worlds created displeased God. He found them too full of darkness, and so he destroyed them. But fragments of these primordial universes linger in the world, looking for any source of energy to cling to. When we sin, we give power to these husks and thus bring evil into the world. I have often wondered, What if those primordial worlds that God smashed contained living beings, with conscious thoughts? What would they think of their Creator who smashed their only home? They might have been imperfect, but did they deserve their fate, since it was the Creator who made them that way in the first place? It is this idea which inspired me to write King of Shards.

The Myth Today

Today many Jews practice Tikkun Olam, or Repairing of the World. They posit that by doing righteous acts and following the commandments of Torah, they “raise holy sparks” and hasten the Messianic era. Some don’t believe in the coming Messiah or the notion of “holy sparks,” but continue to practice the art of Tikkun Olam as a secular form of social justice. There is even a website and magazine, run by activist Rabbi Michael Lerner, Tikkun.org, devoted to this very idea of healing the world.

Kabbalah has also become very popular in the last several decades around the world, with many books being written on its complex and esoteric mythology. One of its central tenets is the concept of the Sephirot, or divine vessels, which were first elaborated in the Zohar.

It’s also interesting to consider how this creation myth in some curious ways parallels the Big Bang theory. There is a great void in space, and within that void there comes a titanic explosion. The explosion spreads hot “sparks,” which slowly cool to form the universe we know. A coincidence? Or did Isaac Luria, intuit something about the universe in his studies and long nights of meditating on reality? It’s interesting to ponder, either way.

I find the idea of the Shattered Vessels is a fascinating one and full of diverse and colorful ideas on the history of creation. To me it suggests an early awareness that the world, contrary to other theological thought, isn’t perfect (perhaps absorbing some ideas from Gnosticism) and the theory arose as an answer to that: The world is imperfect, and it is our job as humans to perfect it. I rather like that.

Tomorrow’s myth: The Great Bird, Ziz.

5 Pingbacks